Post by Mal Fayers, B Phty APAM Physiotherapist

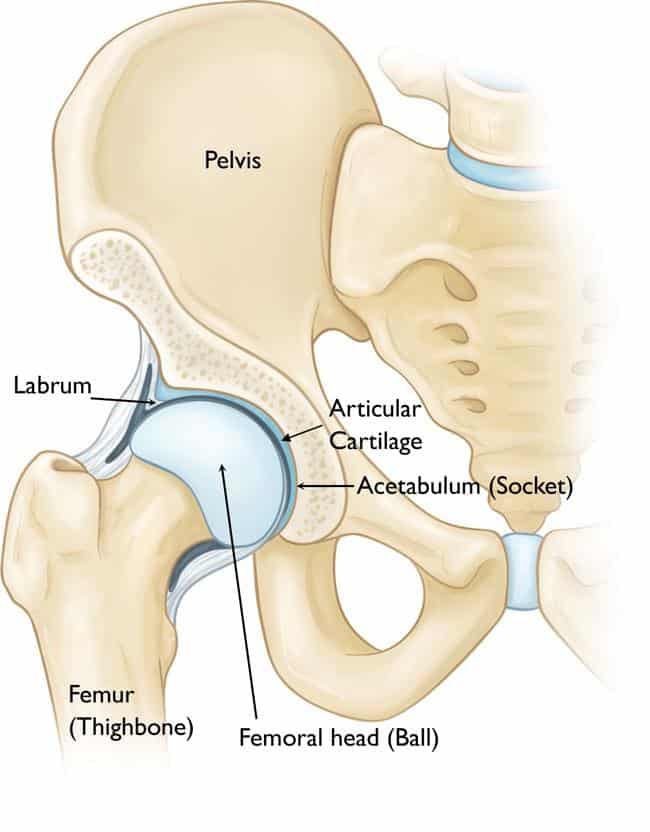

The hip joint is the largest ball and socket joint in our body. It connects the pelvis to the thigh bone and is responsible for a multitude of movements and muscular attachments. Whilst it is incredibly durable, the hip is very susceptible to injury through acute traumatic events, overuse, and through anatomical variations from person to person.

Lateral hip pain varies greatly in presentation. When people think of hip pain, the first thought is arthritis. Whilst this is a common culprit for older (and occasionally younger) populations, hip pain is often far more complex than simple ‘wear and tear’.

[Hip anatomy – ball & socket joint]

Overuse injuries of the hip are incredibly common. They can be due to sudden increases in training load or constant, repetitive movements over time. Both tight muscles and strength imbalances around the pelvis play an important role in the cause of overuse injuries. One such injury is greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), an overarching diagnosis for tendinopathy of the local tendons and inflammation of their

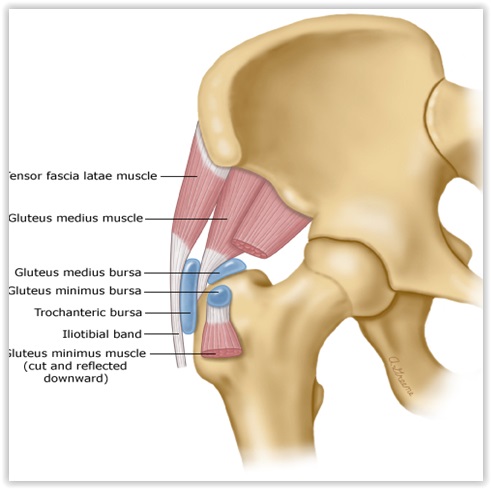

associated bursae. The greater trochanter is a large bony protrusion on the side of the hip and is the attachment site for the tendons of five muscles (gluteus medius and minimus, piriformis, and obturator’s internus and externus). Surrounding the greater trochanter and the tendons are fluid filled sacs called bursa, which are responsible for reducing friction between bone and the surrounding soft tissue. Lateral hip pain was once simply diagnosed and treated as hip bursitis. However, on ultrasound where signs of bursitis were present, a majority (92%!) were found to have no hip symptoms whatsoever. Whilst the terminology is interchangeable, research now tells us that GTPS is most commonly tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons.

[Gluteal tendons (white) and bursae (blue)]

Tendinopathy is the umbrella term for injury to the tendon. There are two relevant stages of tendinopathy; reactive/early disrepair and degenerative/late disrepair. In the reactive stage, the tendon has the capacity to rehabilitate to pain-free, normal function. However, in the degenerative stage, the tendon structure has already changed, meaning rehabilitation is aimed at addressing tendon function and the ability to handle load in order to become pain free. As such, it is very important to rehab as early as possible.

The gluteal tendons are particularly susceptible to injury due to the acute angle of attachment of the tendons onto the greater trochanter. When there are repetitive loads to the tendons or the attachment site, a tendinopathy occurs, leading to pain and disability.

GTPS can affect any age and gender. However, it is most commonly seen in women aged 40-60. Research suggests a number of causes of GTPS, including anatomical variations of the neck of femur, increased body fat, weak gluteal muscles, poor control of the hip and pelvis, poor neuromotor control (the brain not sending signals to the muscles to do their jobs), and poor posture. GTPS also has a link to lower back and knee pain.

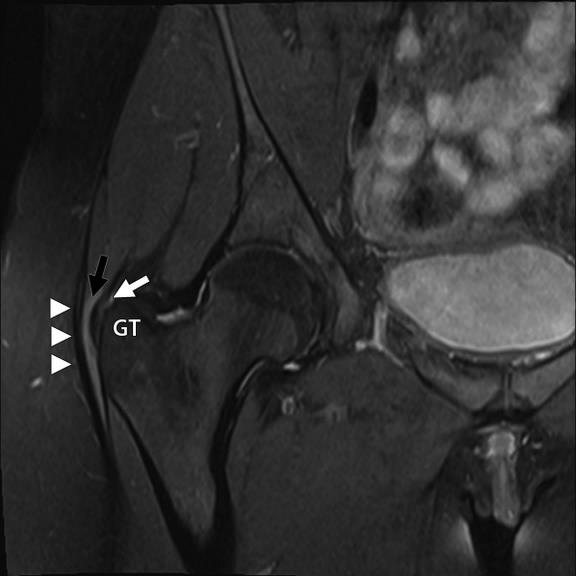

[MRI of gluteal tendinopathy – increased opacity (whiteness) of tendon indicating tendon injury]

As such, when you have lateral hip pain, it is important to see your physiotherapist for a comprehensive assessment. After a detailed history is taken, including any changes to activity or training load, your physio will perform a physical exam to identify any underlying causes, including poor control of the lumbar spine and pelvis (lumbopelvic stability), lower limb weakness, and muscle tightness and dysfunction, all of which play a role in causing GTPS. A battery of clinical tests will also be performed in order to confirm the diagnosis of GTPS and ensure no other potential pathologies of the hip are present. It is important that the underlying cause of your GTPS is identified and treated as early as possible, which will decrease the chances of recurrence in the future. An MRI may also be performed in order to confirm the diagnosis of GTPS and to indicate the stage of tendinopathy.

Initially, treatment will be aimed at improving symptoms and managing tendon load. This begins with short-term training load reduction, the use of ice and anti-inflammatories (in consultation with your GP) to help alleviate pain and modifications to daily lifestyle habits. These include sleeping with a pillow in between the legs, avoiding sleeping on the affected side, and avoiding sitting cross legged. Tendon specific exercises will also be prescribed. Initially, this will involve isometric exercises to improve pain and maintain the loading ability of the tendon. As pain settles, increased tendon loading will begin with eccentric exercises, followed by resistance exercises as you continue to progress. Additionally, your physio will develop a home exercise program to improve lumbopelvic stability and muscular weakness, tightness, and dysfunction.

As symptoms improve, your physiotherapist will work in consultation with you on a return to training and sport, in keeping with your training and performance goals. As weeks progress, training intensity will increase as the tendons respond positively to the incremental increases in load, and exercises will be targeted to your return to sport or activity. Eventually, you will be able to return to sport with a pain-free hip and improved movement patterning, helping to ensure your GTPS is less likely to reoccur.

Call RHP Physiotherapy at our Kelvin Grove clinic on (07) 3856 5566, or our Nathan clinic on (07) 3184 6844, and book in to see one of our physiotherapists today!